NJAL’s Katja Horvat questions whether fashion photography has a future amidst the radical shifts in publishing. How does our current technological milieu fundamentally alter fashion photography as we know it? Is the ubiquity of smartphones, advance in-image editing applications, social media, and the rise of fashion film rendering the canonised medium of fashion photography obsolete?

The evolution of photography over the last two centuries demonstrates the medium’s capacity for vigour and until recently, it’s showed no sign of internal exhaustion. Yet, if we focus on fashion photography today, one could say it’s visibly exhausted in an era of constant technological acceleration. What’s going on right now is the paroxysm of styles, and an array of new publishing formats redefining what was formerly known as photography, to the contemporary realm of “image-making”. Where there is no a priori criterion and where there is no enshrined narrative for fashion imagery, everyone can become a photographer, and with the right resources, a successful one. Yet “success” doesn’t always equate to “skill”.

Now more than ever, our current technological milieu is altering the market, but the majority of buzzy young names in fashion photography will not pass the test of time. Simon Rasmussen, Stylist & Creative Director/Editor in Chief of Office Magazine NYC, says: “Everybody can overnight become a fashion photographer and we see younger and younger photographers shooting editorials and executing look books and such. The successful ones already have a huge following due to their knowledge of how social media works and the power within.” It would seem that though these young photographers might not lack the talent or the creative mindset, it remains increasingly difficult for these photographers to sustain the momentum of their social-media accrued hype for more than a fleeting moment. If these photographers are making work for the immaterial age, and it solely relies on the currency of “likes”, will they have the energy to pursue their practice in the long run?

Hype in the most contemporary sense is a product of social media. Internet based social media has made it possible for one person to communicate with thousands of other people and migrate content to micro-communities aggregated under niche, and organised hashtags. In the context of mass-marketing, social media has reoriented our economy of attention and the entire landscape of traditional advertising and publishing has had to rapidly adapt.

Proenza Schouler’s Jack McCollough, while speaking to BoF Founder Imran Amed even said, “Blogs posting things about us, going viral, spiraling throughout the internet and it has an extraordinary impact on the business.” So, what we are witnessing can be described as a revolution – one that can be felt all around us, even if we are not actively involved in it. It’s dominating all aspects of our world, even the way we use Internet.

Saša Štucin, Co-Founder of Soft Baroque and Editor at Large at POP Magazine, recounts an opinionated post by Matthews Leifheit on Facebook. Leifheit referenced New York Times photography critic Teju Cole in conversation with Geoff Dyer, Ivan Vladislavic and Laura Weller. The conversation addressed Instagram and the impact of mass imagery on social media will have on photography. Leifheit responded to the photographer’s negative response to their contemporary condition and questioned, “If you’re tired of the billions of photographs that the kids are taking, then maybe you’re tired of photography?”

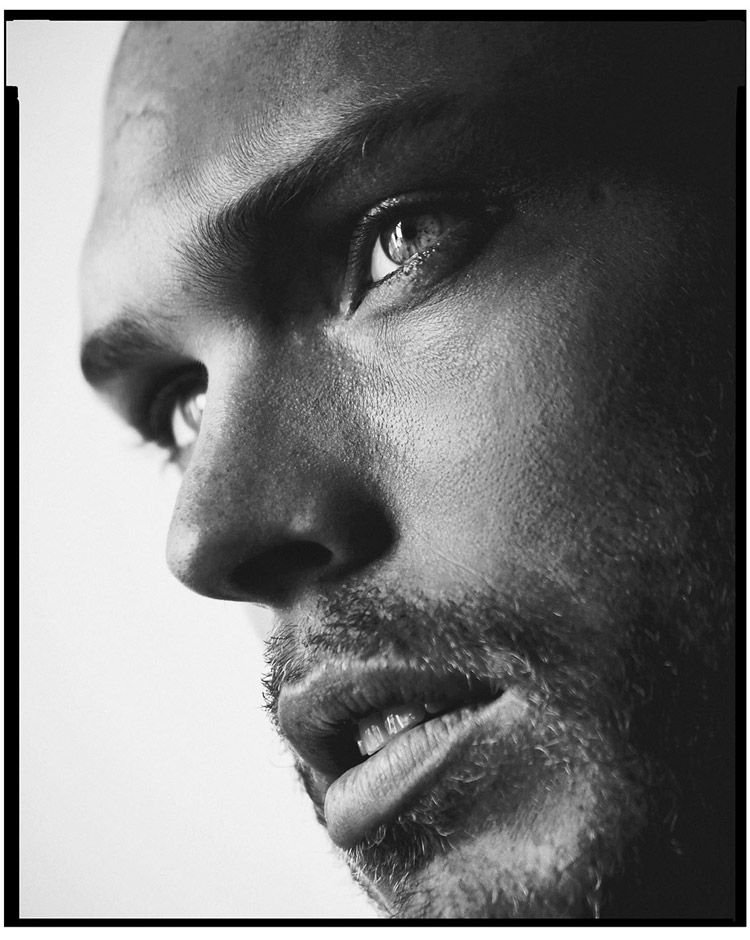

Though Štucin doesn’t wholly agree, she did say that Leifheit’s statement is the “realest thing I’ve heard in response to that conversation.” Štucin does believe that society has to progress in tandem with technology. “This is 2015, and there’s a very rich, intense and incessant output of photography going on around us, and all the time. Photography is not just, you know, black and white stuff made with plate glass cameras by old white dudes,” she says bluntly. Štucin alludes to a distinction between “high” and “low” photography today that seems somewhat ironic, given the historic struggle photography endured to become a rarefied artistic medium in the first place. At its inception, photography was never considered art and firmly sidelined to the realm of science.

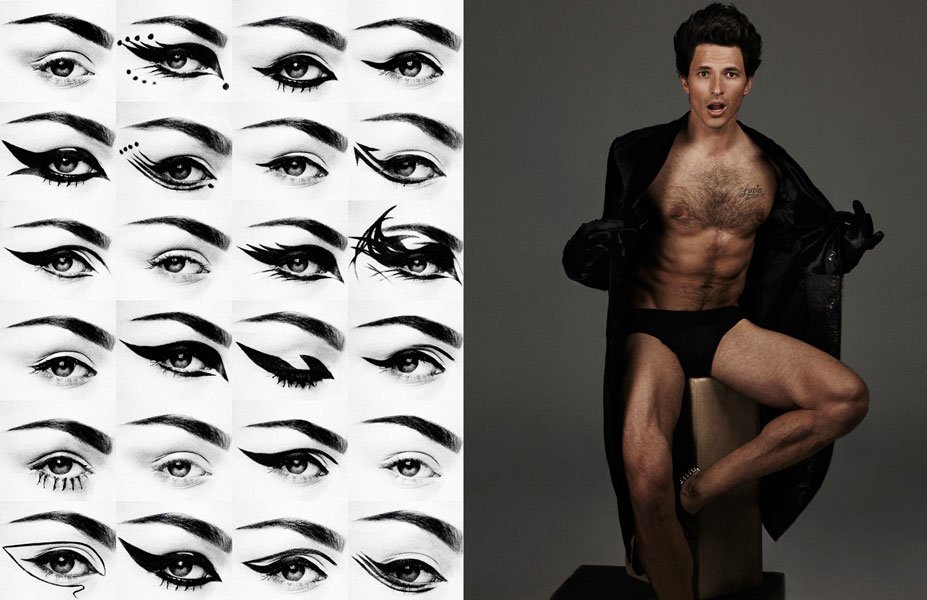

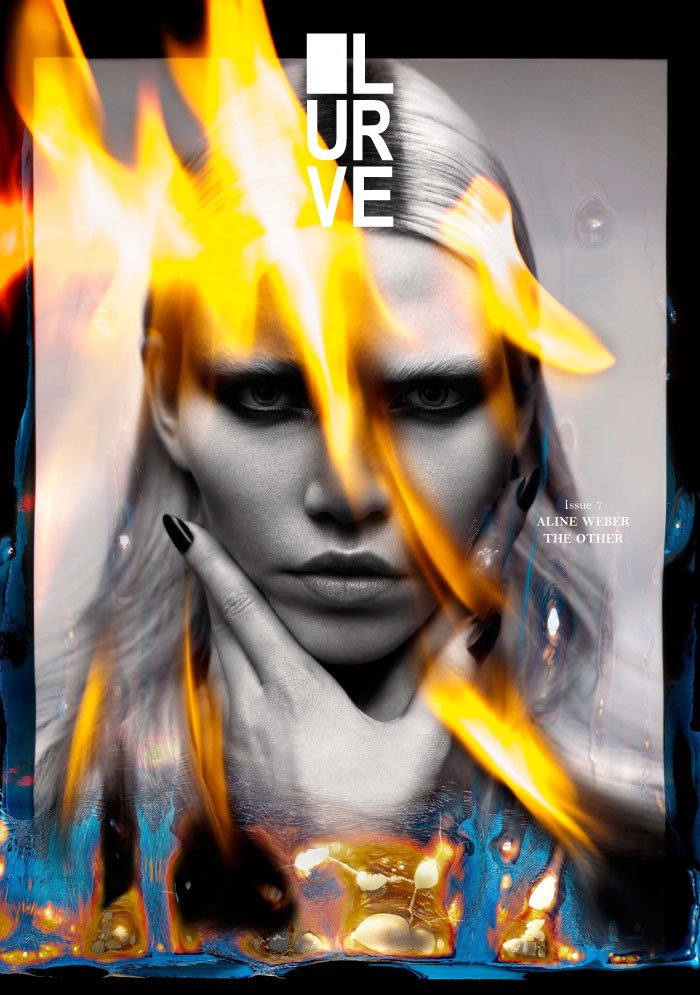

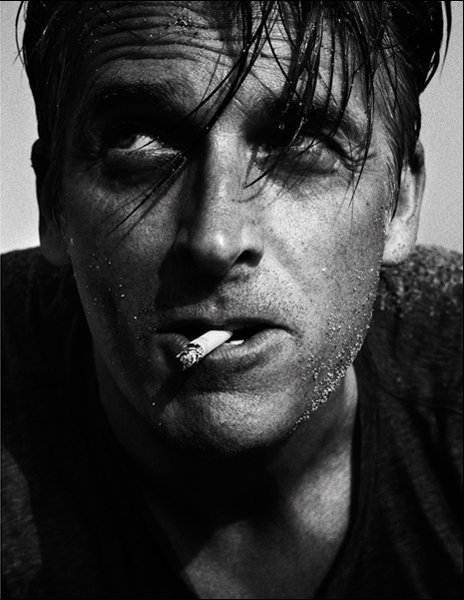

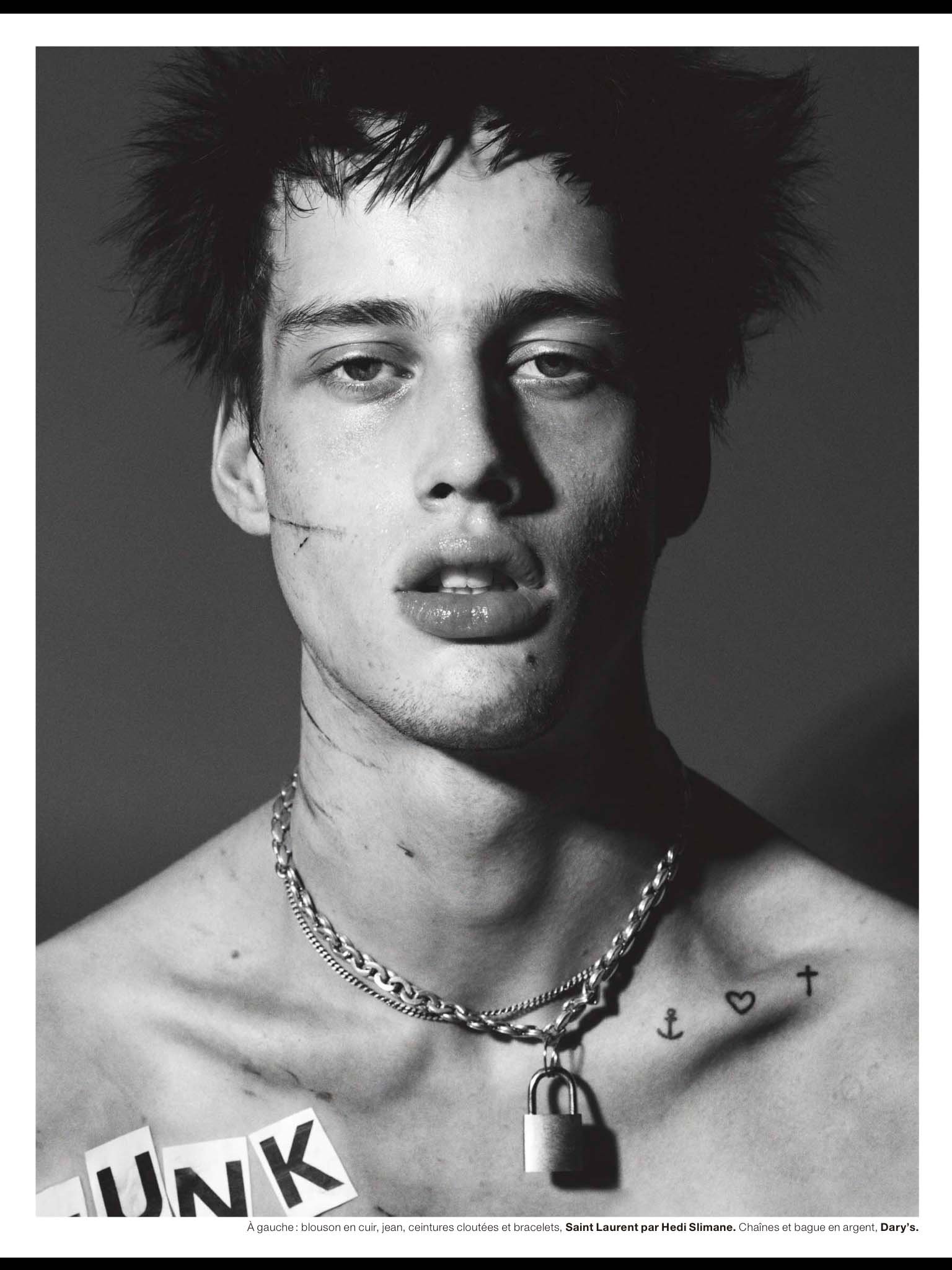

Today, the medium of fashion photography is fractured, given the rise of fashion film as the industry’s new medium of choice for both artistic expression and campaign advertising. Yet, there will always be true grit photographers committed to preserving the art of still photography, even when the very notion becomes archaic. There will be photographers invested in the medium’s rampant technological acceleration, as there are photographers committed to preserving by-gone analogue aesthetics and their outdated apparatuses. Today, the large proportion of photographers working inside in fashion, have to be more flexible with their skills and knowledge, as well as aware of the effects, and the social-media applications which will proliferate attention, and once again adapt to new shifts in the industry’s parameters for fashion photography.

Social media democracy, and its inherent accessibility has made the fashion industry, and the consumer as diverse as ever. The fashion industry, largely because of social media is defined only by front-end, consumer-facing innovation. No longer are the rarefied print pages of a niche fashion bible ripe ground for brands to visually communicate with their customers. Today, 91% of all consumer engagement happens on Instagram, and it’s this very application as well as its limitations that have redefined the parameters of traditional photography and presentation. Tech-enabled methodologies deliver different results as we know it, all visual information is pushed, pulled and shared on every media platform there is, and as a result, quality is no longer heralded over quantity. This era of accelerationism churns out content at an aggressive rate, and discourages smarter, and informed decision-making by its very design.

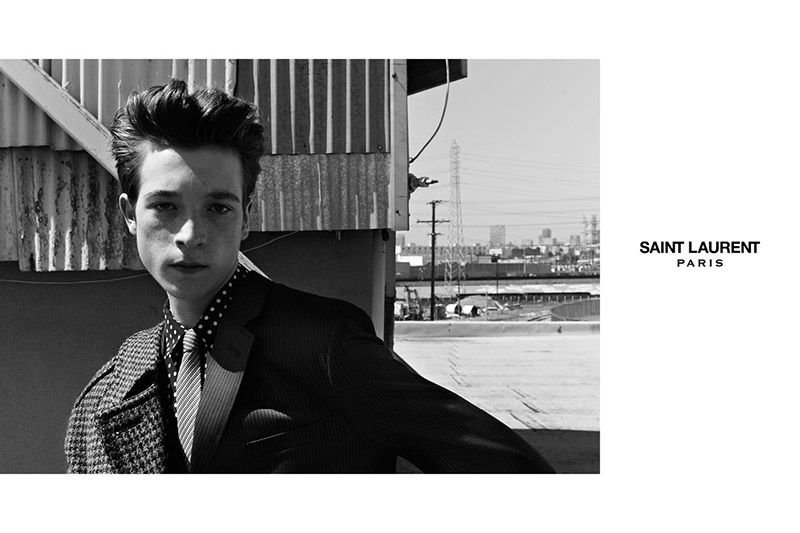

Simon Rasmussen says, “I truly believe that traditional photography is still alive and it’s a part of my job as an Editor for a print magazine to maintain a high level and demonstrate excellent quality of control in all images we put out there.” While Rasmussen is quick to champion emerging talent across all creative disciplines, he also notes the “huge difference between young, self-taught photographers versus an experienced photographer who went through school and assisted for a decade.” The distinct differences separating these creative generations isn’t just quality, but everything from professionalism, technique, aesthetic affinity, and a more general approach.

Perhaps the most glaring difference for Rasmussen is the younger photographer’s propensity for social media, “I hope that younger photographers aren’t just booked for their Instagram clout anymore,” he says. There’s no doubt a social media “clout-score” will be important to some, but Rasmussen explicitly prefers that his young photographer do not even have an Instagram account. “Luckily taste and aesthetics is still something you have to have and cannot just simply copy and repost,” adds Rasmussen.

Do the fundamental changes in fashion photography as a medium reflect the paradigm shifts unfolding in wider society? The context of creativity has drastically changed; it’s no longer simply about the medium or a single artistic discipline but a cross-pollination. Photography can readily align itself with fine art, architecture, politics, just as fashion photography emerged as a distinct medium amongst photography’s wider interdisciplinary engagement. However, what has changed is that the formula of skill, knowledge and process is no longer a criterion for the medium’s success. Instead, its ruled by an immediate currency of reaction, and its ability to capture and harvest data, which in a fashion context—translates into sales.

It’s this unapologetic commercial alignment that’s also driving a younger generation to preserve the archaic process and practice of traditional photography. Though it’s less about conservation for these younger creatives, the tanglible labour, and mosaic processes of physical photography is a bold, artistic statement in the age of immaterialty. It’s about carving out a niche aesthetic and cultural cachet that sets you apart from the Instagram-ready masses. This cross-pollination of process and practice, and by-gone aesthetics with metaphysical modernism is resulting in a hybrid of new aesthetics and anti-aesthetic styles, where traditional techniques and contemporary technological freedoms intermingle. Saša Štucin adds that these contemporary conditions are symptomatic of, “thinking about what photography could be if we forget what we know about photography entireley.”

The metamorphosis of the photographic medium is forgetting its preconceptions without ignoring them. While we can’t necessarily predict what the fashion industry will look like in the future, one thing remains certain, and that’s documentating fashion will become even more intricate and complex in its design and dissemination.